French outside France

The most important regions in which texts written in French circulated, were copied and indeed composed in the Middle Ages were as follows:

- England and the British Isles more generally. It is tempting to see 1066 as the main factor here, since the Norman Conquest obviously embedded a francophone (though not strictly speaking 'French') aristocracy and clergy in the British Isles, with lasting impact. However, we have strong evidence for a francophone presence in England and for sustained cross-channel exchange and traffic (which must have entailed multilingualism) before the Conquest (on which see Lewis 1995 and Tyler 2013). Furthermore, after the conquest matters are complex since the Norman aristocracy became anglophone within a few generations. While the use of French in England was tenacious in some spheres through to the 16th c. (the law, for example) the number of French speakers, their competence, and their reasons for speaking or writing French varied considerably between 1066 and the later Middle Ages. While England was to a large extent the main driver of written francophone culture in the 12th c. and texts in French remain central to English literary and political culture throughout the Middle Ages (see Butterfield 2009), French was always a minority language in the British Isles and restricted to quite specific registers and speech communities (Cannon 2013).

Flanders and the Low Countries. Both the political frontiers between the kingdom of France and the Empire and shifting alliances meant that the status of such territories as the counties of Flanders or Hainault altered and were often contested through the Middle Ages. The Flemish nobility and Flemish merchants used French for both cultural and pragmatic purposes, while some religious communities, even when located firmly within Flemish-/Dutch-speaking territories, routinely used French alongside Flemish/Dutch and Latin. To speak of 'francophone communities' in Flanders and the Low Countries would nevertheless be misleading; it would be more accurate to say that many communities some distance from the apparent linguistic frontier were in some circumstances and for some purposes multilingual.

Flanders and the Low Countries. Both the political frontiers between the kingdom of France and the Empire and shifting alliances meant that the status of such territories as the counties of Flanders or Hainault altered and were often contested through the Middle Ages. The Flemish nobility and Flemish merchants used French for both cultural and pragmatic purposes, while some religious communities, even when located firmly within Flemish-/Dutch-speaking territories, routinely used French alongside Flemish/Dutch and Latin. To speak of 'francophone communities' in Flanders and the Low Countries would nevertheless be misleading; it would be more accurate to say that many communities some distance from the apparent linguistic frontier were in some circumstances and for some purposes multilingual.- Italy. There is 12-c. visual evidence (mosaics, wall-paintings) for the circulation of narratives that were probably transmitted in French. From the mid-13th c. onwards, we have concrete material evidence for centres of francophone literary activity and MS production, initially in Genoa, Pisa, and the Veneto, then subsequently in Northern Italy more generally and also in Naples (Meyer 1904). Italy was crucial to the MS traditions of certain important literary texts written in French, some of which are included in our corpus: many chansons de geste, the Roman de Troie, the Histoire ancienne, the Tristan en prose, Guiron le courtois. Many histories of Italian literature assert a decline in interest in texts in French, or code this socially as increasingly restricted to the bourgeoisie (and therefore lower status) once Dante, Boccaccio and Petrarch are available to Italian readers. However, MS production indicates a continued appetite for texts in French on the part of Italian readers through to the 15th c. Furthermore, several extremely successful texts written in French are the work of Italians (for example Brunetto Latini, Marco Polo, Martin da Canale and Rustichello da Pisa).

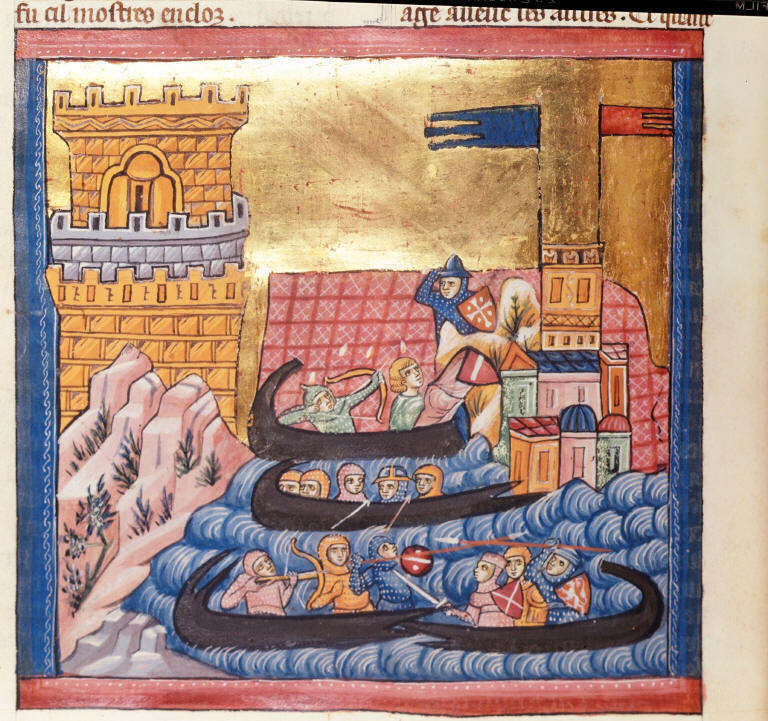

The Eastern Mediterranean. The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem was established in 1099 after the first Crusade and survived until the Fall of Acre in 1291. The majority of the Western Europeans who founded and subsequently settled in the Kingdom of Jerusalem were either of Norman extraction and therefore francophone, or from francophone Flanders (Minervini 2010). Occitan speakers were present in large numbers in the contiguous County of Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Edessa, but the Norman and Northern French/Low Countries presences were nonetheless important. In the 13th and 14th c., both the Principalities of Cyprus and Morea (in the Peloponnese) had francophone rulers and both also took in francophone refugees from the Crusader states after the fall of Acre. There were important scriptoria producing MSS with texts in French in the Latin Kingdom, particularly Acre (Folda 2005), and some significant texts in French are known to have been composed in Cyprus and Morea. However, as with the British Isles, Flanders and Italy, the francophone eastern Mediterranean was profoundly and intrinsically multilingual, with French existing alongside multiple forms of (at least) Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Latin, Occitan, and Persian, often in communities that were also multi-ethnic and multi-faith, communities in which only a relatively small minority had French as a mother tongue.

The Eastern Mediterranean. The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem was established in 1099 after the first Crusade and survived until the Fall of Acre in 1291. The majority of the Western Europeans who founded and subsequently settled in the Kingdom of Jerusalem were either of Norman extraction and therefore francophone, or from francophone Flanders (Minervini 2010). Occitan speakers were present in large numbers in the contiguous County of Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Edessa, but the Norman and Northern French/Low Countries presences were nonetheless important. In the 13th and 14th c., both the Principalities of Cyprus and Morea (in the Peloponnese) had francophone rulers and both also took in francophone refugees from the Crusader states after the fall of Acre. There were important scriptoria producing MSS with texts in French in the Latin Kingdom, particularly Acre (Folda 2005), and some significant texts in French are known to have been composed in Cyprus and Morea. However, as with the British Isles, Flanders and Italy, the francophone eastern Mediterranean was profoundly and intrinsically multilingual, with French existing alongside multiple forms of (at least) Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Latin, Occitan, and Persian, often in communities that were also multi-ethnic and multi-faith, communities in which only a relatively small minority had French as a mother tongue.

We also have evidence for the presence of French texts in the Iberian peninsular, Germany, Scandinavia, and various parts of Eastern Europe. However, the documented evidence consists mainly in the presence of MSS and translations of French texts into other languages. It is less clear that there was any sustained production of MSS of French texts as there was in England, Flanders, Italy, and the Eastern Mediterranean. Our focus is on those parts of Europe where we know French texts were reproduced and read in French rather than translated into other languages.